The Argentine capital is European and South American, sensuous and scatty. It sleeps little and dances all night — and you can now fly there for £600.

Buenos Aires has cafes the way Rome has churches. They are sanctuaries, and you find them on every street corner. More than 70 of them have protected status, the Argentine equivalent of a Bernini portico. They come with black and white floor tiles, bevelled mirrors, carved wood, stained glass, shelves of wine bottles, a hint of the belle époque, a dash of art nouveau — and battered coffee machines that look as if they were imported from Italy in 1932.

Mornings in my pew by the open window in the Bar Britanico, watching the life of the old neighbourhood of San Telmo while enjoying a café cortado and a medialuna pastry, were heaven, the best part of the day. At least until the evening kicked off.

Hang around one of these cafes long enough and you begin to be drawn into the stories and secrets of Buenos Aires. And that’s because the porteños, as the people of Buenos Aires are called, can’t stop talking about their city. Buenos Aires is the central character of their lives: the lover they can’t abandon, difficult, adorable, maddening, endlessly charming.

An elderly woman with a slash of scarlet lipstick tried to show me the difference between tango de salon and tango nuevo, clutching me to her perfumed bosom between the tables while the waiters choked with laughter. Another claimed to know what happened between the deranged colonel and Evita’s corpse. A short man, who insisted he was Napoleon’s only surviving descendant, told me about the man who kept lions in the grounds of his mansion as a security precaution. A dishevelled intellectual gentleman reading the morning copy of La Prensa directed me to the great waterworld of the Tigre Delta.

“You need to get out of the city once a week,” he said. “Or you go crazy.”

I prefer my cities a little on the crazy side. Geneva is meant to be picturesque, with prosperous, well-balanced citizens, but I am not really interested. They tell me Frankfurt is modern and efficient and generally litter-free, but who cares? Give me chaotic Naples or troubled Istanbul or tumultuous Rio, and I am in. When the offer came through to go to Buenos Aires — Norwegian has launched a new direct flight from London, with fares, if you’re lucky, for less than £600 return — I couldn’t resist. The city has the highest proportion of psychoanalysts per head of population on the planet — three times the rate of New York. That sounded perfect.

Part of Buenos Aires’s psychosis is that it is in denial. The city believes it is European. This obsession has led to what analysts might call a divided self — a sense of inferiority when it compares itself to Europe, and feelings of superiority to the rest of South America. Ask a Brazilian and they will happily tell you that Argentinians could commit suicide by jumping off their own egos.

It probably doesn’t help that Buenos Aires has been called the Paris of the South so often that many porteños have come to believe it. But Buenos Aires is far too friendly and far too much fun to be French. The city is a rollercoaster of Old World identities, twisted and exaggerated in the unbridled New World atmosphere.

Spaniards came to style themselves as grand caballeros; Italians emigrated here for the chance to be more Italian; the British came to ride horses, shear sheep and sell beef to Smithfield; the Germans came from the Weimar hoping — hilariously, as it turned out — for order and good governance. Buenos Aires is a city with Neapolitan balconies, Moorish courtyards, English mansions, Gaudi-inspired Catalan domes, New York skyscrapers, French parks and cobbled streets that might belong in old Cairo. Christopher Isherwood called it “the most truly international city in the world”. Most people call it a delightful hybrid, eclectic, beautiful, grubby, vibrant, pretty crazy.

If you could get the city on the analyst’s couch, it would soon be babbling about its childhood. For Buenos Aires, things haven’t quite turned out as hoped. In its youthful heyday, a century ago, it was the capital of the sixth richest country in the world, a promised land with a peso that was soaring above the American dollar. But middle age brought disillusionment and disappointment, with one crisis after another — military coups, falling currency, corruption, hyperinflation, dictatorship — until eventually the whole place was reduced to a tearful Andrew Lloyd Webber musical.

Yet the city seems to have come to terms with its issues. Argentina is stable these days, and Buenos Aires is flourishing. Fizzing with energy, it is one of the few cities I know that can make Rio seem dull. Past economic woes have made everyone an entrepreneur, and it has a hustling creative drive, as well as a determination to have a good time.

I was never sure when porteños slept, because they seemed to be awake at almost any hour of the night. Every evening, the streets of Palermo feel like an extended party, crowded with merry folk eager to drink, dine and dance until dawn. There are fabulous restaurants for every taste and dish, from delicate ceviches to steaks the size of a hat. There are stylish clubs and wine bars and tabled terraces packed with gorgeous people. Hipsters are opening microbreweries — beer is the latest fad — and old-time speakeasies with menus of lethal cocktails. “The porteño sense of fun is what I love about this city,” said an English resident. “Well, that and tango. I have become addicted to tango.”

Moored like a galleon over the 14-lane Avenida 9th of July — a boulevard that makes the Champs-Elysées look like a country lane — is the city’s great showpiece, Teatro Colon. It is one of the greatest opera houses in the world, with marble from Italy, parquet floors from England and architectural echoes from Versailles. This is what Argentina was meant to become: Europe in the New World. But what it actually became was the milonga, the tango club. Opera was just a hand-me-down, someone else’s idea of a good time. Tango is pure porteño.

Having started in the bars and bordellos of the docks, it is dark, troubled, elegant, sexy and more than a little odd. People might enjoy the opera. But they are passionate about tango.

The Argentine novelist Ernesto Sabato said: “Only gringos dance the tango for fun.” And this is what is so odd about tango: it is one of the only dances in the world not meant to express joy. It is passionate but melancholy. The lyrics are all about love, misery and death, while the dancers deploy faces of melodramatic suffering. The pleasure of tango is its licence to be operatically miserable.

At 2am — things kick off late in Buenos Aires — I turned up at an old-fashioned milonga with my date for the evening. Maria was tall and stunning, with an avalanche of hair. A couple of turns on the floor convinced Maria that she would be better to accept invitations from men who were less of a threat to her toes. I sat out a few sets while a series of brilliantined chaps glided her round. The star turn was a short, barrel-chested man whose chin was level with Maria’s cleavage, a position that had her struggling to maintain her serious tango face.

From tango, it is a short step to death. The next morning found me at the great cemetery of Recoleta. In Buenos Aires, they don’t generally bury people. Instead, they store them above ground in mausoleums and elaborate family tombs, among gargoyles, chipped urns and trumpeting cherubs. But for Evita, they made an exception. They buried her several feet down, like nuclear waste.

In life, Evita, the wife of the populist president Juan Peron, inspired fanatical devotion. Three million people filled the streets of Buenos Aires for her funeral when she died of cancer in the summer of 1952, at the age of 33. When Peron was ousted in a military coup three years later, no one was sure what to do with Evita’s perfectly embalmed body.

Unfortunately, it was entrusted to Colonel Moori Koenig. As she was shuttled between various hiding places in Buenos Aires, he became enamoured of the body. Eventually, he was accused of “un-Christian” acts, and the colonel and the corpse had to be separated. Perhaps his therapist was on holiday at the time. Evita’s body was shipped to Milan and buried under a false name. Years later, when it was returned, it was interred here in Recoleta beneath thick steel plates, possibly in case Koenig came looking.

At least that’s how they tell the story at Bar Britanico. The bar’s stories all had the quality of the city itself — by turns sentimental and scandalous, treading a porous line between comedy and tragedy. It was easy to get hooked on them.

My favourite was the millionaire and the lions, set in the late 19th century. Afraid of being burgled, one Eustoquio Diaz Velez installed a couple of the predators on the land around his mansion. Tragedy struck during his daughter’s engagement party, when one of the lions ate her fiancé. We all roared with laughter.

The great Argentine writer Jorge Luis Borges was fond of declaring his love for Buenos Aires. But that’s how most porteños feel. It is a lifelong love affair, the Latin kind, with plate-throwing rows and tears, as well as passionate reconciliations and hysterical protestations of love. That’s the kind of city she is, crazy and adorable.

I got kinda crazy about her myself.

WHERE TO STAY

CasaSur Bellini, in Palermo Chico, has a cool pool and doubles from £115, B&B (casasurhotel.com). In upmarket Recoleta, Hub Porteño is a stylish boutique hotel with the feel of a private club (doubles from £189, B&B; hubporteno.com). Palo Santo is a stylish option in Palermo, with lush gardens, a rooftop pool and a Japanese restaurant (doubles from £75, B&B; palosantohotel.com).

WHERE TO EAT

Napoles, in San Telmo, is an astonishing antiques emporium reimagined as a funky restaurant and bar. You’ll dine among old racing cars and classical statuary (mains from £14; facebook.com/napolesristorante). Odd, perhaps, to recommend a Peruvian restaurant, but La Mar, in Palermo, has a terrace that, on a sunny day, is one of the places to be. The ceviche is unrivalled (mains from £19; lamarcebicheria.com.ar). Don Julio, also in Palermo, is an atmospheric Argentine steakhouse, or parrilla, with a wine cellar of 13,000 bottles. The steaks start at £21, but are so big, they can be split between two (parrilladonjulio.com).

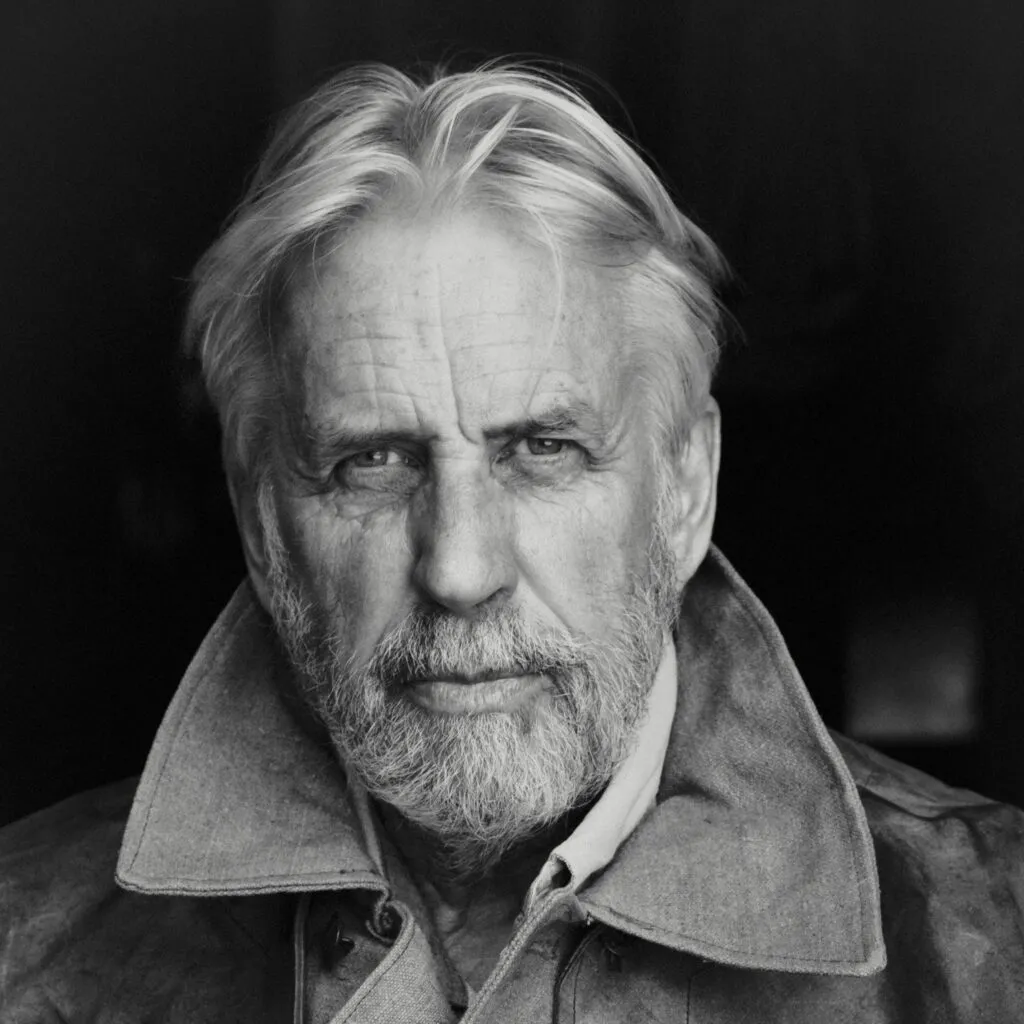

ABOUT THE WRITER

Stanley Stewart is an acclaimed travel writer with over two decades of experience writing for publications on both sides of the Atlantic. He is a regular contributor to The Sunday Times and The Daily Telegraph, where his work has won numerous awards, including Travel Writer of the Year on six occasions. Here for The Times newspaper, he shares his experience of travelling to Buenos Aires, where he was a guest of Plan South America.

Related Stories

Buenos Aires Guide: The Last Word

Where to Eat & Drink in Buenos Aires: A Guide by Sorrel Moseley-Williams

A Solo Road Trip from Buenos Aires to the Chilean Coast with Stanley Stewart – Condé Nast Traveller

Wine Tasting in Argentina: Where to Go and What to Try

@plansouthamerica