“Surrounded by the barren heights of the Andes, the Elqui valley is a verdant linear oasis.”

Stanley Stewart is an acclaimed travel writer with over two decades of experience writing for publications on both sides of the Atlantic. He is a regular contributor to The Sunday Times and The Daily Telegraph, where his work has won numerous awards, including Travel Writer of the Year on six occasions. Here for the FT, he shares his experience of travelling from Chile’s Elqui valley to Argentina as a guest of Plan South America.

Throughout her life, Gabriela Mistral suffered a sense of exile. The first Latin American winner of the Nobel Prize for Literature, she mourned for the landscapes of her childhood. To her, according to one commentator, they were “the true and only world, an almost fabulous land lost in time and space”.

She grew up here, in Chile’s Elqui valley, where I stood on a rock outcrop, vineyards swirling round my feet, gazing toward the heights of the Andes. The valley lies on the edge of the Atacama Desert, tucked among Andean foothills. It could almost be a microcosm of Chile. Long and thin, it stretches from the Pacific some 135 miles to the bleak rising heights of the mountains, a linear oasis trapped between alien forces.

I was heading to Argentina and would follow Mistral’s childhood valley to one of the highest and most spectacular passes in the cordillera, the Paso de Agua Negra at 4,780 metres above sea level. I was travelling with my girlfriend, tousle-haired, almond-eyed, as complex as the landscape. We too were preparing for a kind of exile. It seemed it would be our last journey together.

Our trip had already taken us through the Atacama, one of the driest places on the planet — weather stations in some parts of it have never recorded rain. It is a landscape pared back to elemental form: bizarre mineral lakes, salt flats, bald isolated mountains, hot springs and geysers. Nasa scientists come here to test instruments for future Mars missions.

We travelled south through the Atacama and at Salado bay on the Pacific coast, we found Wara Nomade. If you had been shipwrecked on this coast with a romantic designer, this might be the camp you would create, some cross between Robinson Crusoe’s island and a chic Ibizan love nest. Wara Nomade is a beachcomber’s dream, both handmade and stylishly sophisticated. Consisting of a handful of tents standing on an empty Pacific shore, it is an eclectic collection of tethered awnings, oriental carpets, driftwood, Bali beds, painted tables, sea shells, repurposed doors, flowers, fairy lights, pelican feathers, all filtered through a faultless aesthetic. At night it flickered with candles and antique lanterns. My girlfriend swam, glistening among moonlit waves, and came back as salty as the sea.

While the chef prepared lunches of ceviche and scallops, we kayaked to offshore islands to visit the sea lions and penguins. They were a contrast in temperaments. The sea lions were irritable and quarrelsome. They looked like they wanted to bite one another’s heads off. The penguins were sweet and companionable. They looked like they wanted to hold fins and go for walks together.

Another morning, in the pre-dawn, we went to the great sand sea north of Copiapó. In the dark, beneath canopies of stars, we settled down atop one of the dunes to await the dawn. Gradually the stars were extinguished as the sky lightened and wind-sculpted sands materialised about us, stretching into pale distances. When the sun rose, its first rays ran along the ridge lines like a caress. I thought of Neruda — “Night, snow and sand/Make up the form of my thin country/All silence lies in its long line.”

From Wara we fired up our rented Landcruiser and drove south through the brittle landscapes of the southern Atacama to the old colonial city of La Serena at the mouth of the Elqui valley. Night had fallen and after several hours of empty nothingness, the roundabouts and carriageways and traffic of the city were strangely disturbing. Eventually we found the turning for the Elqui valley, and drove away again into country darkness, leaving the traffic and the city and the desert behind. The road narrowed between adobe walls, our headlights illuminating roadside figures cloaked in dust and ponchos. We turned down a humble lane, past walled orchards and an old church, its cracked bell hanging above the gateway, and arrived at Casa Molle, a luxury oasis whose stylish vernacular architecture sits amid green lawns and orchards, vineyards and infinity pools.

Within minutes of arrival we were ensconced on a terrace with a glass of Chilean wine, a platter of charcuterie and a telescope. Wherever you go in the Elqui valley there seems to be a chap with a telescope. The clarity of its atmosphere has made the valley one of the foremost locations on the planet for observing the stars. Its skies brim with them. Numerous institutions have built their observatories here. The valley is a crossing place, astronomers say, a point of connection between our world and the universe.

Between sips of Malbec, an earnest gentleman, invited by the hotel to explain the mysteries of the universe, had us peering through his eyepiece at the heavens. We looked at Betelgeuse, the bright reddish star at the end of one of Orion’s limbs, the Jewel Box cluster, bright Sirius and the Omega cluster in the Centaurus constellation, which is said to contain millions of individual stars. When the distant galaxies began to make our heads spin, we turned to the more manageable stories of the constellations — Perseus with Medusa’s head, the pirates turned into dolphins, a golden-fleeced lamb, Aquarius pouring his water jar. The Inca too saw figures and stories in these skies. But the forms their stories described were not the constellations but the dark shapes between them.

We woke to a verdant valley. I felt that sense of relief that comes from the arrival in any oasis. We had come from the desert. We stepped out into a morning of birdsong and dappled sun, the smell of water on stone and the soft rustle of wind in leaves.

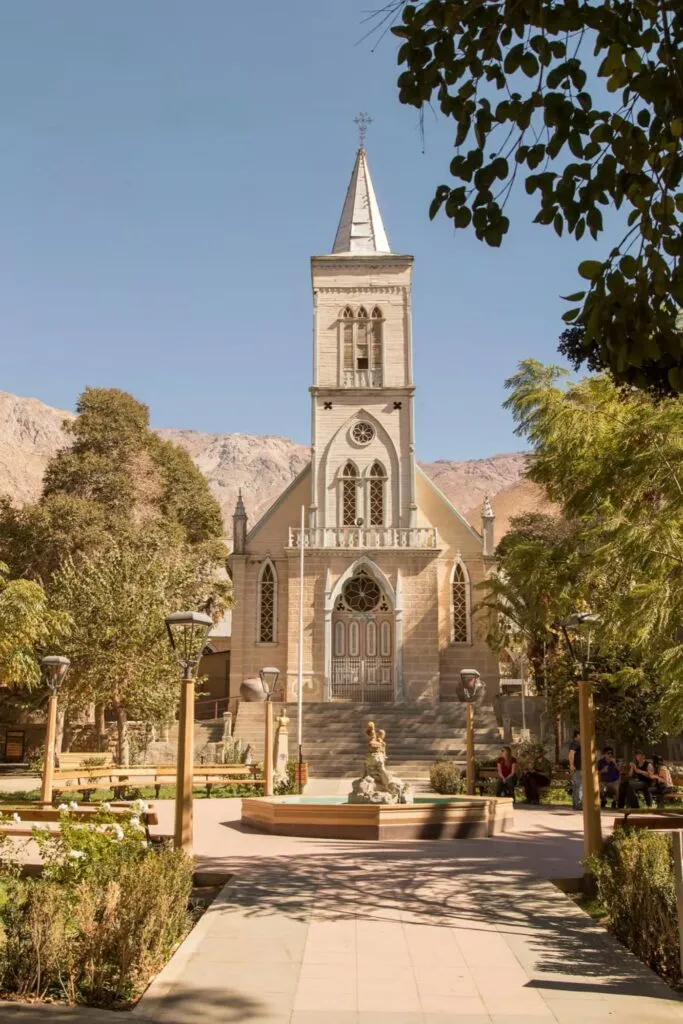

A river bubbles down the Elqui valley, irrigating fields and orchards framed by bleak foothills. The old towns are all tiled roofs and stained adobe walls, ancient churches and cobbled squares. Its orchards are heavy with papayas and avocados and figs. Vineyards cloak the upper slopes. In the town of Vicuña, retro bars and cafés were full of old photographs and coffee machines that looked like they had come from Naples in the 1920s.

A sense of nostalgia filtered down through the pimento trees like dust. The beauty of the valley carries some sweet innocence, even for those who did not pass their childhood here. We ate ice creams together beneath the trees, and my girlfriend said we would think of this moment later and wonder if it was real.

Vicuña is the birthplace of Mistral, and the museum here charts her life as a poet, educator, feminist and diplomat. Her romantic life seems to have had a few hiccups. Her first love killed himself. Her second married someone else. In later life she realised she was focusing on the wrong gender when she found happiness at last with a younger woman.

Beyond Vicuña, the valley narrowed, a thick green belt twisting between bare rose-coloured Andean foothills, the big trees, the meadows and the vineyards a kind of sweet defiance against this wider world of mineral-streaked rock. Pepper trees scattered pink blossoms across the roads. The long walls of houses, painted earthy reds and yellows, framed elaborate wooden doors. We veered up the side valley of the Rio Clara and came to Monte Grande, where Mistral spent most of her childhood.

Mistral died on Long Island in 1957 but had asked for her body to be returned to the Elqui. In a leafy grove we found the grave of “La Gabriela”, as she is known here, among blue convolvulus. “I was happy until I left Monte Grande [at the age of 11],” she wrote. “And then I was never happy again.” Perhaps one shouldn’t argue with the dead but I didn’t believe her. I think I understood her though. Those of us who have travelled far from our origins are all haunted by the idealised landscapes of our childhood, that lost world, part memory and part invention. Absence allows us to remake our past in golden hues.

After Monte Grande, we passed through the village of Pisco Elqui with its numerous pisco distilleries. The Peruvians like to think pisco is theirs but Chileans disagree, and many would say the greatest piscos are distilled from grape skins in this valley. Further along the road, as it degenerated into gravel track, we paused to savour the wines of Viñedos de Alcohuaz, founded only 15 years ago by the renowned Chilean winemaker Marcelo Retamal. He wants to create wines that are an expression of the valley with its high altitude and its granite soils, and insists on all the grapes being trodden by foot. In the stylish tasting room, overseen by a French sommelier, we swilled and sipped and tried to be serious. The top vintages were flinty and bone dry.

Beyond Alcohuaz, the last village of the valley, a guide directed us to the house of Juan Carlos, who had escaped to the Elqui valley from Santiago some six years earlier, in search of stillness. But he had brought the world with him to this remote place. His rambling house was a museum of curios, a cornucopia of objects — condor feathers, French film posters, pre-Inca pottery, modernist paintings, Chinese wardrobes, African drums, Victorian footstools, Mapuche jewellery, Thai Buddhas, Indian tapestries — all apparently for sale. It was a splendidly odd and unexpected encounter. We sat in his sitting room, chatting about Angkor Wat and western African masks and Humphrey Bogart while the Andes filled the views from the windows. Even as we took our leave, he trailed after us with a Spanish hat from Potosi, two serving spoons from Rajasthan, a teddy bear from Dorset.

The following morning we headed for the Paso de Agua Negra over the Andes, following a milky green river beyond the fields and the orchards into bleak canyons. The valley petered out and we entered a less comforting world.

Ahead, the heights of the Andes were rising. On the far bank, tucked against a precipitous rock wall, supported here and there by stonework, was the old Inca road that would have been here when the first conquistadors came clanking through these canyons. There was a perfunctory Chilean customs post, some hours short of the actual frontier, then we drove on into a wilderness of rock.

After a time the road began to climb, rising out of the narrow canyons to slant across bare slopes. Suddenly we seemed to have left everything behind — villages, houses, people, cars, birdsong, trees, greenery. The world had grown vast and empty. The river had vanished. The Inca highway had foundered some time ago. Colossal bareheaded mountains were rising to meet us. Climbing at impossible angles, the gravel road was the only feature on these slopes, turning and twisting like a creature trying to gain a foothold. It seemed both heroic and vulnerable as it climbed doggedly upward to the Andean watershed. Each curve brought new vistas of summits tumbling away into further and further reaches. Far below, I spotted a group of vicuña trotting towards the green smudge of a spring. High above, in a pale sky, a pair of condors turned.

At the top of the pass, a frame stood over the road announcing the international border. There was no one here, no houses, no border posts, no sign of human life at all, only the gravel road. Chileans and Argentines both deemed the pass far too high for permanent presence. I was conscious of the thin air and aware of breathing it. It felt tangible, something precise and delicate. We became light-headed and disconnected and giddy, dazed by altitude. Mountain summits rode away in every direction.

Then we fell into Argentina. The road twisted downward for a couple of hours across spectacular ranges. Finally, we reached the Argentine border post where an official in a dog-eared uniform said we were the only car that day.

Even when they don’t denote international borders, mountain passes still feel like watersheds. In Barreal in Argentina, a day later, my girlfriend waited for the bus to Buenos Aires. When it wheezed to a stop, she climbed aboard and took her seat while I stood on the roadside feeling bereft. It was the end of something.

The bus went away in a spiral of dust, carrying happiness with it, and in that moment the Elqui valley became the sweetest place on Earth, the lost world where everything had been fine and easy and intimate, where we laughed together about nothing and shared stories about other lives and drank wine on terraces watching the constellations drop towards the distant ocean. I wondered if it was real.

Related Stories

A Solo Road Trip from Buenos Aires to the Chilean Coast with Stanley Stewart – Condé Nast Traveller

Exploring Chile’s Wine Country: Top Vineyards & Lodges

Late Nights and Tall Tales in Buenos Aires with Stanley Stewart – The Times

Rafting Chile’s Wild Futaleufú with Stanley Stewart – Travel + Leisure

@plansouthamerica